Plein Air

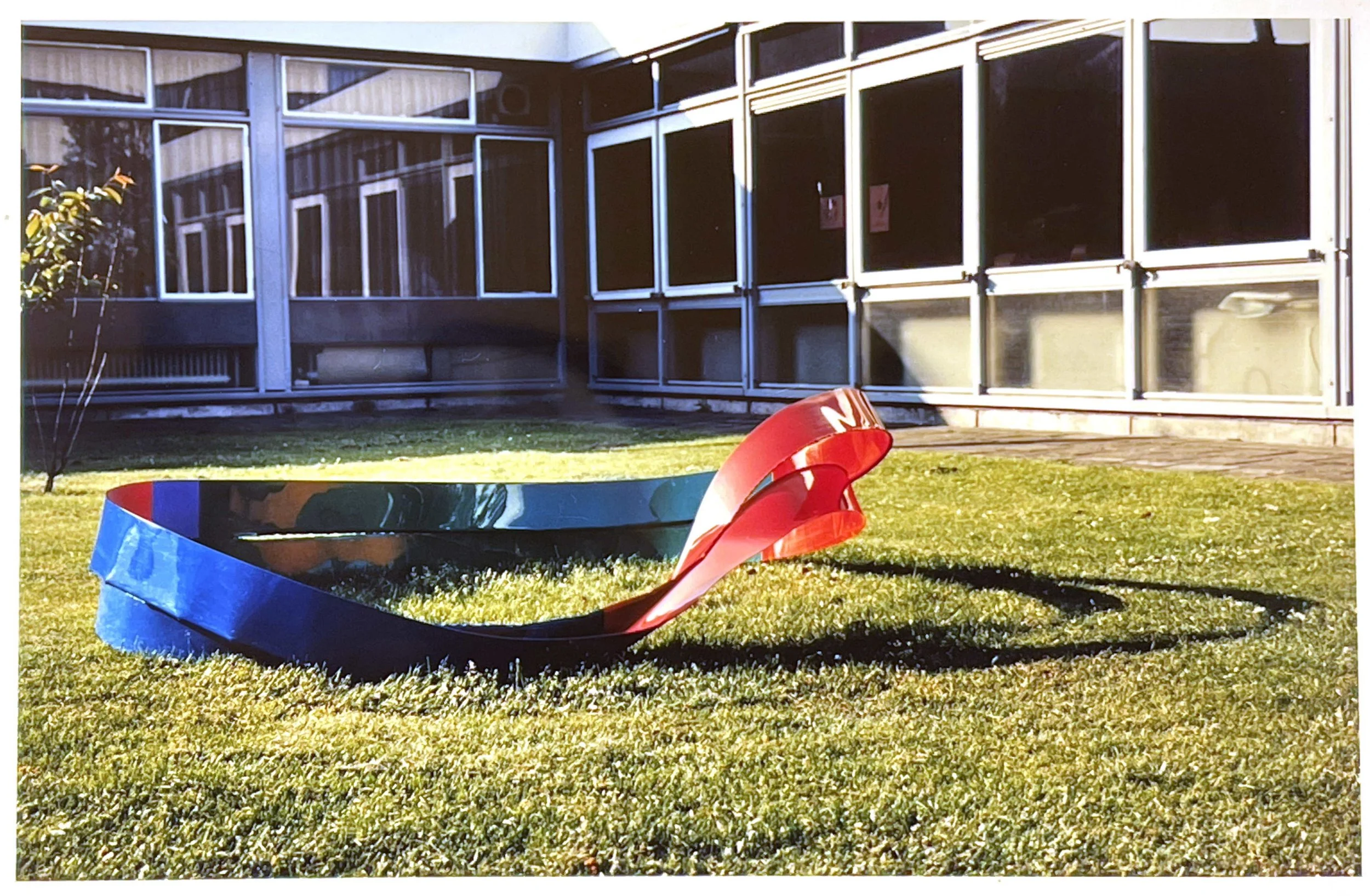

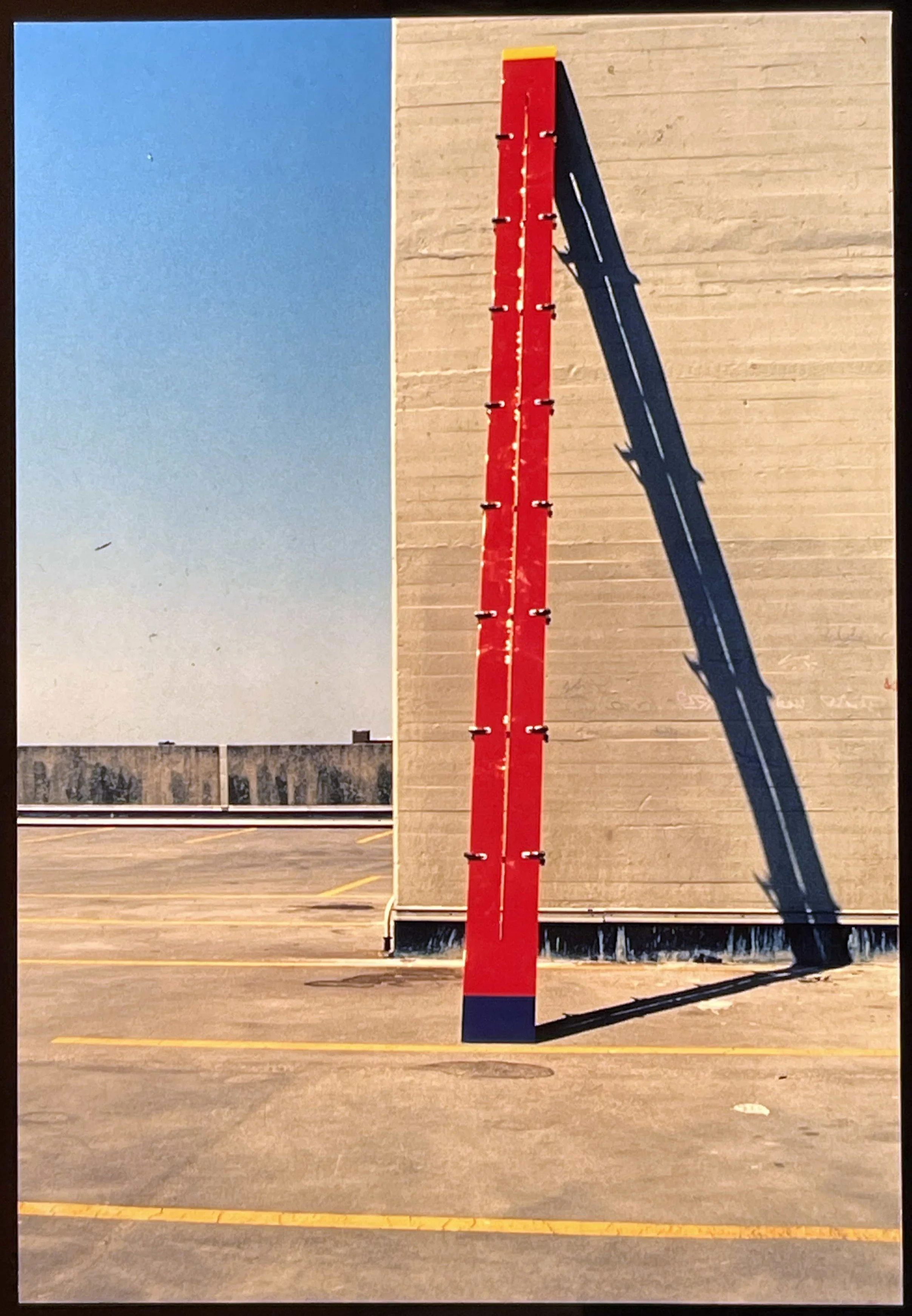

“For the final work I want to discuss as an example of the ever-changing content, I’ll tie in with current events: the exhibition that will open on September 9 at the Exposorium van de Universiteit van Humanistiek on the Drift in Utrecht. At that exhibition, nine sculptures will be shown that Roland Van den Berghe created in 1986–87 in response to the disastrous damage inflicted on Barnett Newman’s Who’s afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III (1966–67) on March 21, 1986, at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. The sculptures have previously barely been seen. For the first time—right after their completion—they were shown for a day and a half, from Saturday afternoon May 23 to Sunday May 24, 1987, on the roof of the parking garage at Marnixstraat 250 in Amsterdam. Then again during the summer of the following year on the outdoor grounds of the paint factory Sikkens in Sassenheim (who, together with art collector Jo Eyk from Wylre, sponsored the realization of the series). After that, only photographic documents of the works were shown at several exhibitions. The two aforementioned venues are not considered established exhibition locations, let alone frequently visited for the fame of the artist. The works are not recent, but almost no one has seen them in person.

They can be seen as the Phoenix rising from the ashes of damage and destruction. In his creation, the artist made no reference to the facts: neither to the damage itself, nor to the sentencing of the perpetrator, nor to the decision to restore the work (instead of the replacement by a replica as proposed by him and two friends). He transcended this level of factuality with a creative process centered on the meanings of the artwork, as they could be experienced before the damage, and afterward. The results of that process will hopefully make a greater audience reflect during the upcoming exhibition than was possible at the time.

Photo Plein Air, rooftop of parking garage in Amsterdam, 1987. Photographer unknown.

As for the modality in which Van den Berghe’s visual reaction took shape, it can be noted that his work had never before assumed such a pure and museal character. It radiates color and is clear in its form. That simplicity and clarity, however, have been hard-won, something you can feel in the work. And yet—this is a quality of modern art in general, when it’s good—the sculptures evoke all kinds of questions, questions that can be posed in many ways. Some of them can be answered clearly and directly, but others are veiled behind the outer brilliance. Why spirals? Why metal? In which incisions have been made? Such questions can be answered unambiguously, because Van den Berghe used a photograph of Barnett Newman’s studio as the basis for the invention of his sculptures. That studio contained rows of small and large paint cans, the material source from which the artworks emerged through transformation. And with a nod to the fatal fate that befell the painting, the can opener—eye-opener—is introduced both literally and figuratively.

Such signs are very direct, maybe even vulgar, but they gain their depth through a visual reference to another layer: the reference to the image of the tearing of the Temple Curtain at the moment of Redemption—the biblical parallel to the Phoenix myth. Many of the titles of his works refer to names and events recorded in the Bible and the Talmud, such a source of inspiration for Barnett Newman. At the same time, there are allusions to more recent events and opinions in the art world. For instance, Newman’s position with respect to European art, of which he considered the work of Mondrian a final expression. But there are also questions raised that are more difficult or even impossible to answer. These remain enclosed within the image, like an Abatur—the title of the final work in the series: the eye enclosed within itself. Questions which, alongside the gift of beauty, perhaps offer the best of what contemplation of a work of art can bring.”

Translated from the Dutch text: 1992, Roland Van den Berghe, Abatur – het in zichzelf besloten oog by Jean Leering, in Arte Factum, June–July–August 1992.

Photo Plein Air, rooftop of parking garage in Amsterdam, 1987. Photographer unknown.

Timeline

1986

Damage inflicted on Barnett Newman’s Who's afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III (1967) at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam

1987

Plein Air, on the roof of Europarking, Marnixstraat 250, Amsterdam, May 23–24

Presented by Hugues Boekraad, Jean Leering, and Job Knap

1988

Plein Air, on the premises of Sikkens-AKZO coatings BV, Sassenheim

Presented by the C.I.R.C.

1990

Een blik op Horizontaal en Verticaal, Galerie d’Eendt, (Anniversary special 1960–1990), Amsterdam

The sculpture Esther was shown, along with a series of photographic registrations (cibachromes) of the nine sculptures

1991

Plein Air Info, Galerie d’Eendt, Amsterdam

1991

Plein Air Info, Iona Stichting, Amsterdam

An overview of letters (published in 1992 in VALISE), newspaper articles, and visual materials

1992

Zoeloe meets Indian, in collaboration with Eldert Willems

The series of cibachromes of the nine sculptures

1992

Plein Air Info, University of Humanistic Studies, Utrecht

With introductory texts by Fons Elders, Jean Leering, and Ernst van de Wetering

1992

Publication of Valise, an artwork in book form, Domein M.B., Amsterdam

1993

Lezing Plein Air Info, Auditorium MuHKA, Museum of Contemporary Art, Antwerp

1993

Omzetting-representatie, exhibition at the Werkplaats voor Beeldende Kunst, Borne

Page from sketchbook, reference to Plein Air, 1987.